I worked for John Deere headquarters for 34 years in corporate communications. Toward the end of my service, I had the good fortune to author the coffee-table corporate history book, Genuine Value: The John Deere Journey. (You can buy a signed copy in Classifieds).

This is the opening chapter of the book. I wrote it as a “fictional memoir,” based on extensive research I did in the John Deere Archive. Once I felt steeped in the life of John Deere based on letters and other historical artifacts, I wrote this chapter as if I were John Deere, the man, speaking as if he were still alive. (Yes, it was an daunting self-imposed assignment.

Our very talented designer, Michael McMillan, added to the seeming authenticity of this chapter by placing my words for Mr. Deere in an antique book and photographing it for the six spreads the text occupied in the book.

Here's what each of the six spreads looked like:

Here's the text as it appears in the book:

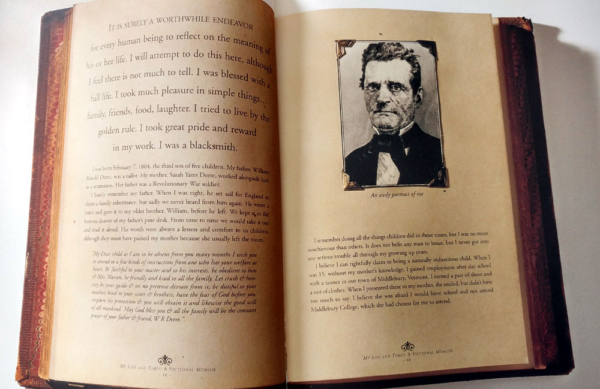

It is surely a worthwhile endeavor for every human being to reflect on the meaning of his or her life. I will attempt to do this here, although I feel there is not much to tell. I was blessed with a full life. I took much pleasure in simple things … family, friends, food, laughter. I tried to live by the golden rule. I took great pride and reward in my work. I was a blacksmith.

I was born February 7, 1804, the third son of five children. My father, William Rinold Deere, was a tailor. My mother, Sarah Yates Deere, worked alongside him as a seamstress. Her father was a Revolutionary War soldier.

I barely remember my father. When I was eight, he set sail for England to claim a family inheritance, but sadly we never heard from him again. He wrote a letter and gave it to my older brother, William, before he left. We kept it in the bottom drawer of my father’s pine desk. From time to time we would take it out and read it aloud. His words were always a lesson and comfort to us children, although they must have pained my mother because she usually left the room.

“My Dear child as I am to be absent from you many months I wish you to attend to a few kinds of instruction from one who has your welfare at heart. Be faithful to your master and to his interests, be obedient to him & Mrs. Warren, be friendly and kind to all the family. Let truth & honesty be your guide & on no pretense deviate from it, be dutiful to your mother, kind to your sister & brothers, have the fear of God before you, implore his protection & you will obtain it and likewise the good will of all mankind. “May God bless you & all the family will be the constant prayer of your father & friend, W R Deere.”

I remember doing all the things children did in those times, but I was no more mischievous than others. It does not befit any man to boast, but I never got into any serious trouble all through my growing up years.

I believe I can rightfully claim to being a naturally industrious child. When I was 15, without my mother’s knowledge, I gained employment after day school with a tanner in our town of Middlebury, Vermont. I earned a pair of shoes and a suit of clothes. When I presented these to my mother, she smiled, but didn’t have too much to say. I believe she was afraid I would leave school and not attend Middlebury College, which she had chosen for me to attend.

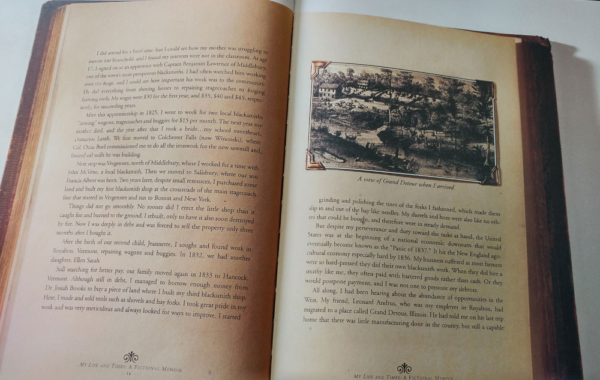

I did attend for a brief time, but I could see how my mother was struggling to sustain our household, and I found my interests were not in the classroom. At age 17, I signed on as an apprentice with Captain Benjamin Lawrence of Middlebury, one of the town’s most prosperous blacksmiths. I had often watched him working over the forge, and I could see how important his work was to the community. He did everything from shoeing horses to repairing stagecoaches to forging farming tools. My wages were $30 for the first year; and $35, $40, & $45 respectively for succeeding years.

After this apprenticeship in 1825, I went to work for two local blacksmiths “ironing” wagons, stagecoaches, and buggies for $15 per month. The next year my mother died, and the year after that I took a bride … my school sweetheart, Demarius Lamb. We first moved to Colchester Falls (now Winooski), where Col. Ozias Buel commissioned me to do all the ironwork for the new sawmill and linseed-oil mills he was building.

Next stop was Vergennes, north of Middlebury, where I worked for a time with John McVene, a local blacksmith. Then we moved to Salisbury, where our son Francis Albert was born. Two years later, despite small resources, I purchased some land and built my first blacksmith shop at the crossroads of the main stagecoach line that started in Vergennes and ran to Boston and New York.

Things did not go smoothly. No sooner did I erect the little shop than it caught fire and burned to the ground. I rebuilt, only to have it also soon destroyed by fire. Now I was deeply in debt and was forced to sell the property only three months after I bought it.

After the birth of our second child, Jeannette, I sought and found work in Royalton, Vermont, repairing wagons and buggies. In 1832, we had another daughter, Ellen Sarah.

Still searching for better pay, our family moved again in 1833 to Hancock, Vermont. Although still in debt, I managed to borrow enough money from Dr. Josiah Brooks to buy a piece of land where I built my third blacksmith shop. Here, I made and sold tools such as shovels and hayforks. I took great pride in my work and was very meticulous and always looked for ways to improve. I started grinding and polishing the tines of the forks I fashioned, which made them slip in and out of the hay like needles. My shovels and hoes were also like no others that could be bought, and therefore were in steady demand.

But despite my perseverance and duty toward the tasks at hand, the United States was at the beginning of a national economic downturn that would eventually become known as the “Panic of 1837.” It hit the New England agricultural economy especially hard by 1836. My business suffered, as most farmers were so hard-pressed they did their own blacksmith work. When they did hire a smithy like me, they often paid with bartered goods rather than cash. Or they would postpone payment, and I was not one to pressure my debtors.

All along, I had been hearing about the abundance of opportunities in the West. My friend, Leonard Andrus, who was my employer in Royalton, had migrated to a place called Grand Detour, Illinois. He had told me on his last trip home that there was little manufacturing done in the county, but still a capable mechanic would have a fair field open for his enterprise. As winter approached in 1836, I could see no future in Vermont. I packed up a few things and kissed my wife and family farewell. I was bound for Illinois.

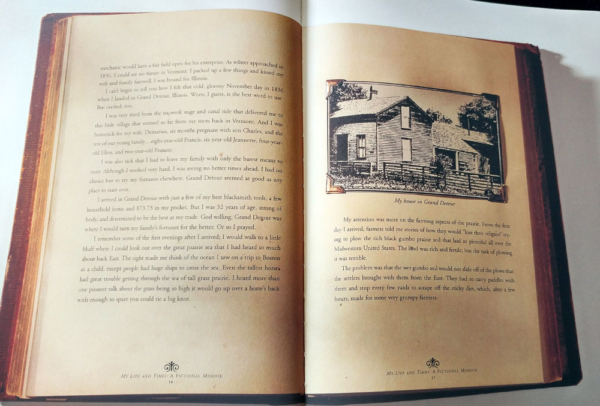

I can’t begin to tell you how I felt that cold, gloomy November day in 1836 when I landed in Grand Detour, Illinois. Worn, I guess, is the best word to use. But excited, too. I was very tired from the six-week stage and canal ride that delivered me to this little village that seemed so far from my roots back in Vermont. And I was homesick for my wife, Demarius, six-months pregnant with son Charles, and the rest of our young family … eight-year-old Francis, six-year-old Jeannette, four-year-old Ellen, and two-year-old Frances.

I was also sick that I had to leave my family with only the barest means to exist. Although I worked very hard, I was seeing no better times ahead. I had no choice but to try my fortunes elsewhere. Grand Detour seemed as good as any place to start over. I arrived in Grand Detour with just a few of my best blacksmith tools, a few household items, and $73.73 in my pocket. But I was 32 years of age, strong of body, and determined to be the best at my trade. God willing, Grand Detour was where I would turn my family’s fortunes for the better. Or so I prayed.

I remember some of the first evenings after I arrived; I would walk to a little bluff where I could look out over the great prairie sea that I had heard so much about back East. The sight made me think of the ocean I saw on a trip to Boston as a child, except people had huge ships to cross the sea. Even the tallest horses had great trouble getting through the sea of tall grass prairie. I heard more than one pioneer talk about the grass being so high it would go up over a horse’s back with enough to spare you could tie a big knot.

My attention was more on the farming aspects of the prairie. From the first day I arrived, farmers told me stories of how they would “lose their religion” trying to plow the rich black gumbo prairie soil that laid so plentiful all over the Midwestern United States.

The land was rich and fertile, but the task of plowing it was terrible.

The problem was that the wet gumbo soil would not slide off of the plows that the settlers brought with them from the East. They had to carry paddles with them and stop every few yards to scrape off the sticky dirt, which, after a few hours, made for some very grumpy farmers.

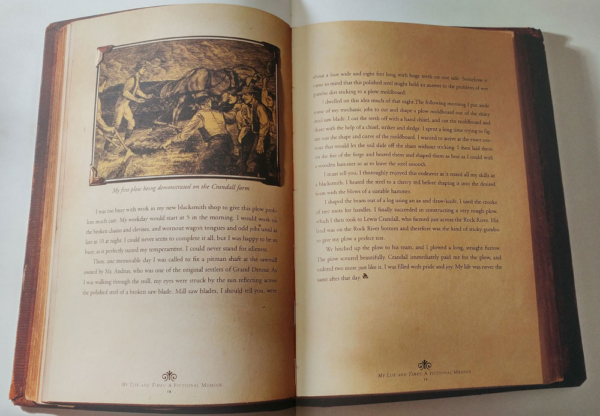

I was too busy with work in my new blacksmith shop to give this plow problem much care. My workday would start at 5 in the morning. I would work on the broken chains and clevises, and worn-out wagon tongues and odd jobs until as late as 10 at night. I could never seem to complete it all, but I was happy to be so busy as it perfectly suited my temperament. I could never stand for idleness.

Then one memorable day I was called to fix a pitman shaft at the sawmill owned by Mr. Andrus, who was one of the original settlers of Grand Detour. As I was walking through the mill, my eyes were struck by the sun reflecting across the polished steel of a broken saw blade. Mill saw blades, I should tell you, were about a foot wide and eight feet long with huge teeth on one side. Somehow it came to mind that this polished steel might hold an answer to the problem of wet gumbo dirt sticking to a plow moldboard.

I dwelled on this idea much of that night. The following morning I put aside some of my mechanic jobs to cut and shape a plow moldboard out of the shiny steel saw blade. I cut the teeth off with a hand chisel, and cut the moldboard and share with the help of a chisel, striker, and sledge. I spent a long time trying to figure out the shape and curve of the moldboard. I wanted to arrive at the exact contour that would let the soil slide off the share without sticking. I then laid them on the fire of the forge and heated them and shaped them as best as I could with a wooden hammer so as to leave the steel smooth.

I must tell you, I thoroughly enjoyed this endeavor as it tested all my skills as a blacksmith. I heated the steel to a cherry red before shaping it into the desired form with the blows of a sizeable hammer.

I shaped the beam out of a log using an ax and draw-knife. I used the crooks of tree roots for handles. I finally succeeded in constructing a very rough plow, which I then took to Lewis Crandall, who farmed just across the Rock River. His land was on the Rock River bottom and therefore was the kind of sticky gumbo to give my plow a perfect test.

We hitched up the plow to his team, and I plowed a long, straight furrow. The plow scoured beautifully. Crandall immediately paid me for the plow, and ordered two more just like it. I was filled with pride and joy. My life was never the same after that day.